Options to the People

One thing I learned about accessibility over the years is that it is not the goal to optimize for certain disabilities but rather to provide options for users. Having numerous and diverse options can enable someone to use a piece of software. For example the option to navigate a website via keyboard alone instead of a mouse. Or the option to be able to jump to the main content of a page via a so called skip link. Or the option to crank up the font size on a website via your browser settings and not have it break the site completely. In effect, you are not only making a thing more accessible to users with certain disabilities. You are designing it to be usable for everyone (Universal Design).

Video games are kind of paradoxical when it comes to accessibility. On the one hand they are highly interactive and often timing-based, so they are inherently more inaccessible than a static website for example. But on the other hand when you take a look at most games they quite often have pretty extensive sets of options you can change to make the game look, play or sound differently.

Although options were always present in video games it is only during the last couple of years that mainstream game developers have started building specific accessibility options into their games.

The reason for this only coming so late is still the general lack of awareness for digital accessibility. For video games in particular I had to check my own awareness too.

As I mentioned options make a game look, play or sound differently. This loosely maps to the broad categories of disabilities:

- Vision: low vision, color blindness, blindness, etc.

- Motor: low dexterity, hand injuries, muscle diseases, paraplegia, etc.

- Hearing: low hearing, deafness, etc.

- Cognitive: learning disabilities, autistic spectrum, etc.

So what options can you provide in video games so that more players can enjoy your game? The answer is it depends on your game. Video game interfaces tend to be more experimental or are at least highly custom with each game. But the principles for accessible and universal design can be applied the same way as anywhere else. A complete guideline for accessible video games would break the scope of any one article and also such guidelines already exist (see the bottom of this article), so I just want to highlight 3 examples of accessibility problems and solutions in video games.

Perceivability of In-Game Text and UI

One of my personal top issues is the legibility of text in video games. For context: I’m fortunate enough to have good vision and no need for glasses. Still I often find myself squinting at the very low font sizes in some games, for example when I’m playing in front of my TV screen which sits 2 meters in front of me. If the game does not provide an option for increasing font size, then I can still just go and sit closer to the screen. Inconvenient for me, but you can imagine how this becomes a critical problem for people with low vision.

The latest God of War (2018) was criticized by a lot of players for having too tiny fonts in the menus. For a game that is exclusive to consoles and thus very likely to be played on a TV which usually is at a certain distance to a player this is a usability disaster. The game devs later patched in an option to increase the font size marginally.

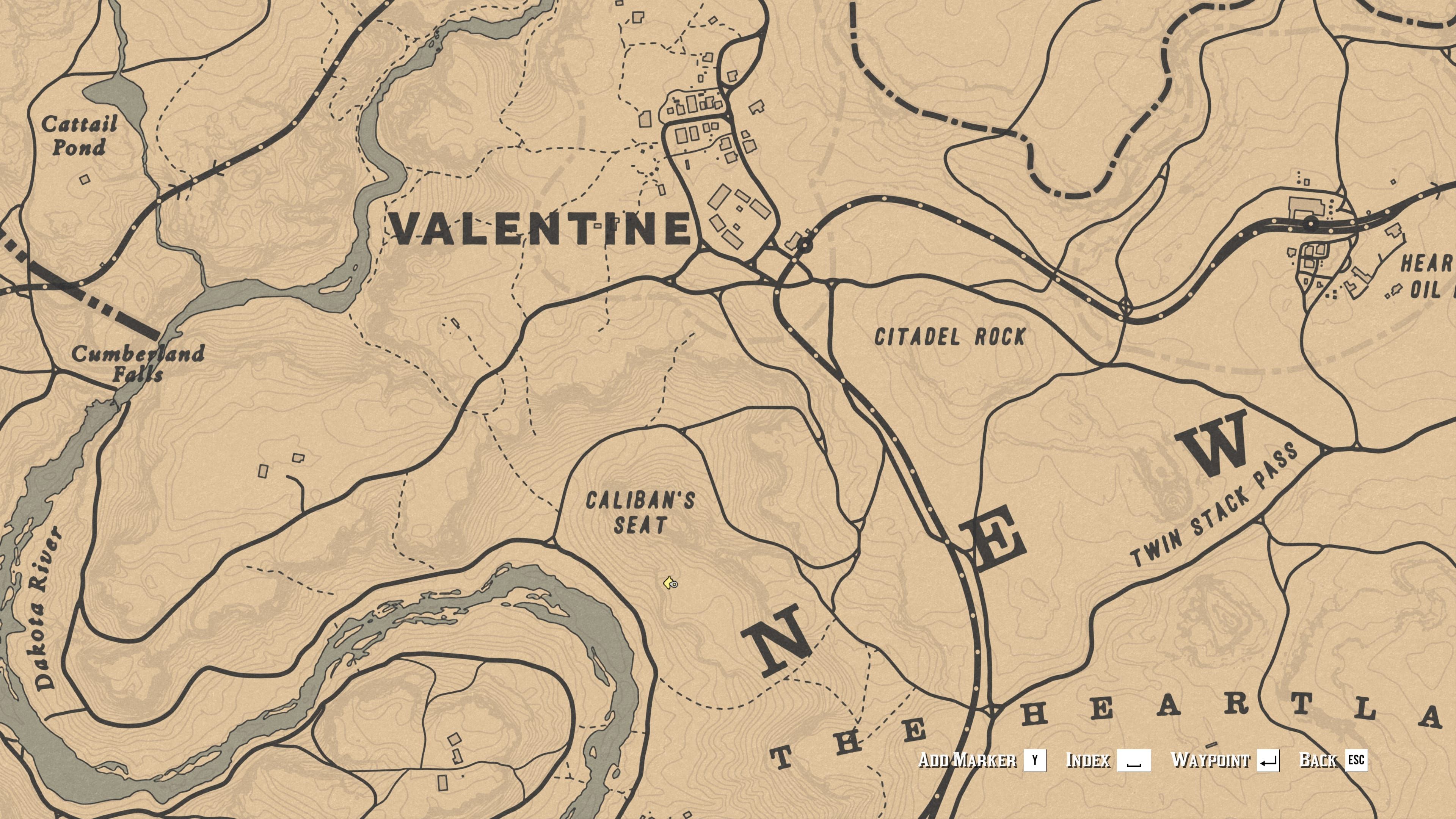

In Red Dead Redemption II, a game that features a vast area of very realistic and detailed North American landscapes, one essential tool is the in-game map that you can open to understand your location and where your next mission is. Here the problem is not only tiny text on the map but even icon markers are so small you might not immediately find them.

If you are a sighted person could you immediately find where the player on the map is on the above screenshot? If no, you’re not alone. In case you couldn’t find it, try clicking the image to load a big size version.

Other games have extensive HUD’s (Head-up-Display) that display constant information to the player. RPGs (Role Playing Games) often rely on constantly showing you status information about the character you are playing in order to have an overview about the situation at any time. Some of these games allow scaling up the whole HUD-UI by a desired factor via a slider in the game options.

For example in The Elder Scrolls Online the whole HUD-UI can be scaled.

Color Design

Accessible design principles are often universal. For instance the following applies in general in accessible design:

Don’t convey information with color alone.

Or in other words, if you are using color to distinguish different things also think about using text or iconography to make the difference apparent.

Imagine a team-based competitive game in which your team plays against an enemy team and the only means to distinguish between friends and foes is that one is shown with a green highlight and the other one with a red one. And now imagine you are one of 8% of the Northern European male population that has red-green color blindness. A key component of your game does not work for 8% of your players.

There are two ways around this. Either you strictly follow the above-mentioned principle and highlight not only with color but in addition with other patterns (icons, text, etc.). Or you could allow players to change these colors in the game options to colors that work for them. Overwatch a team-based competitive game by Blizzard allows for this.

Control Customization

Controls are core to a video game. They differ strongly between games and almost each game needs to be learned anew by a player. The input devices and how they are used often share common patterns. On PC players often use keyboard and mouse with certain keys having a high importance: WASD keys, space bar, etc., are often used in 3D games. Number keys might be used in strategy games more often. On consoles the standard controllers of Xbox, PlayStation and Nintendo by now have converged to all have two analog sticks and 4 shoulder buttons.

For players with low dexterity or for example missing limbs it is key that the standard controls on both keyboard and console controllers can be remapped to other buttons. By the way on PC remapping controls for keyboard input has been common for decades. For consoles this has historically been way stricter with only some games allowing to switch between different control mapping presets.

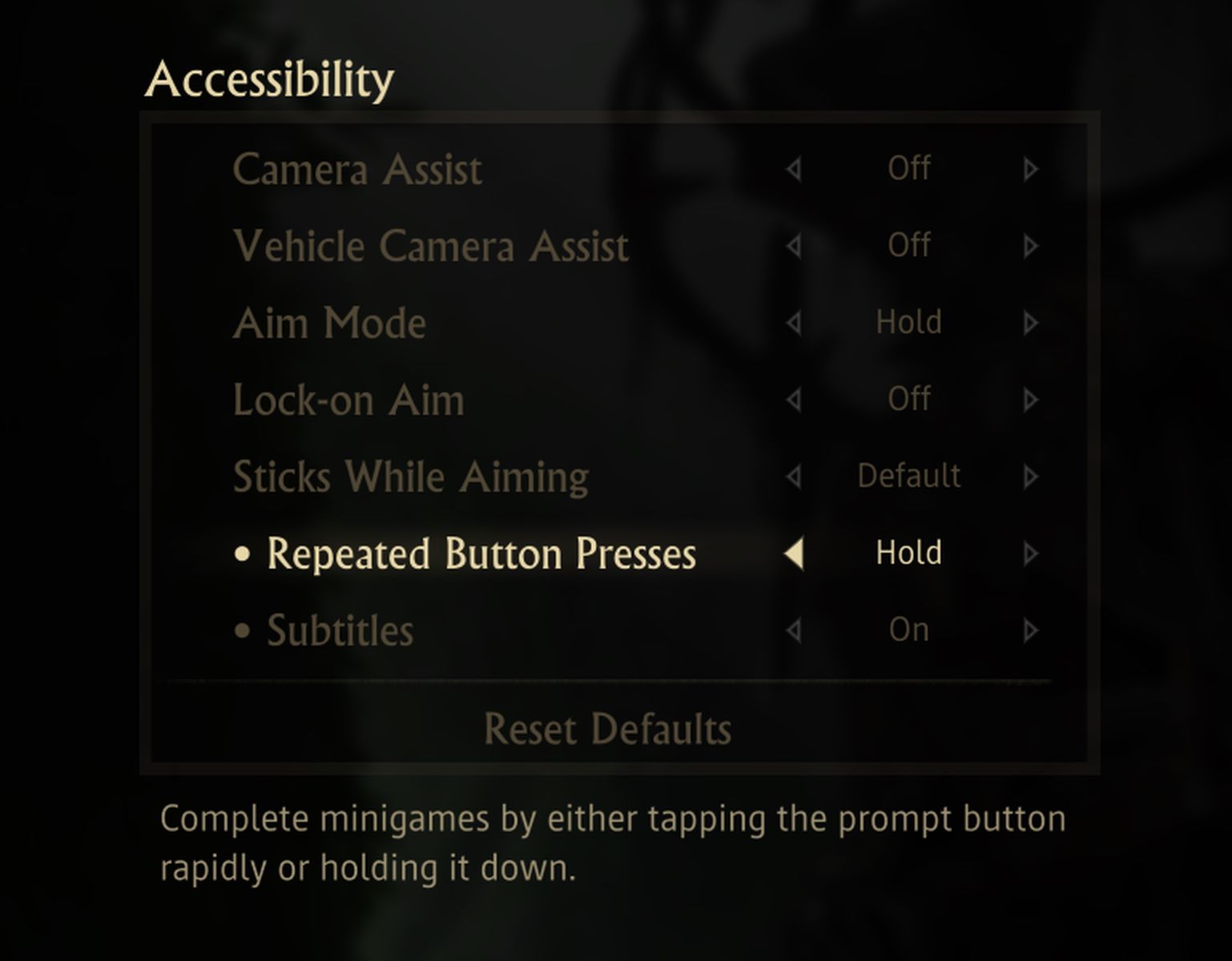

Next to the need for remapping controls there is another important consideration here. Over the last decades, console games especially, popularized certain input patterns like repeated fast pressing of a button to simulate a difficult task for the virtual character or aiming at something in-game by holding one controller shoulder button while using an analogue stick to manipulate the game’s camera. These high dexterity tasks can pose a problem and completely exclude players from getting past parts of a game if they are not physically able to do these required finger acrobatics. Not to mention that some of these hand movements also can cause repetitive strain injuries. Something that players as they get older (like me) might be confronted with.

Uncharted 4, a very mainstream action title on the PlayStation, has options dealing with these problems in the form of input alternatives. They allow players not to have to press a button repeatedly for example but to hold that button for the duration of a sequence. Or they make the aiming “auto-lock” on game objects without the need to hold a shoulder button and adjust the camera with an analogue stick at the same time.

Options to the People

If you read all of this and are maybe wondering why I call out all these issues here under the topic of accessibility and not as usability problems — well they are closely related.

Good usability makes things more accessible. Accessible design is by default more usable.

You achieve both when you give options to the people.

As I mentioned these are just a few of many considerations to not exclude players from video games. If you want to dive into more details you can check out this amazing guideline which was compiled by a group of experts from the industry: Game Accessibility Guidelines.